Paul Graham’s startup survival rules: working the right way to make real money

Check out Paul Graham’s startup survival rules formulated in five points.

Investors want to find businesses to invest as much as businesses want investors

Get the feedback first: don’t spend millions developing something nobody wants

Whether you've raised your first $10,000 or $1,000,000, be frugal

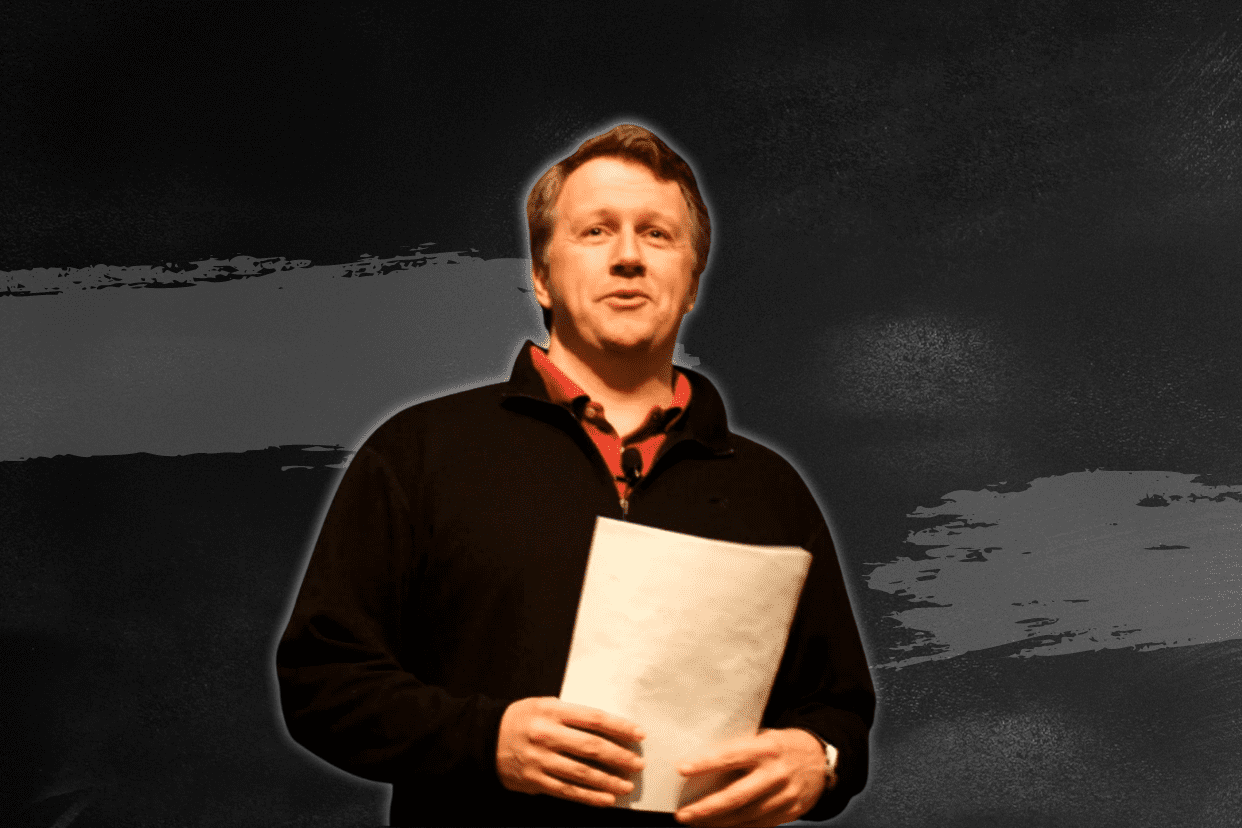

Silicon Valley investor Paul Graham is widely known as the founder of the Y Combinator. Since 2005, the Y Combinator has funded over 2,000 startups, including Airbnb, Dropbox, Stripe and Reddit. He is also the author of numerous essays on launching startups. These essays garnered over 25 million reads last year.

We have gathered some of his most quoted tips on keeping your startup afloat. From finding the right people to the intricacies of raising money. As a renowned industry expert, his suggestions are useful to innovators who are just starting out, as well as businesses that have already survived their first years and are seeking ways to expand.

Find the money

The truth is, you will need funds to make anything happen. The first thing you’ll need is a few tens of thousands of dollars to pay your expenses while you develop a prototype. Raising seed capital is no rocket science — at least you can always get a quick response.

As Graham points out, there are plenty of funding opportunities around:

“Once you’ve got a company set up, it may seem presumptuous to go knocking on the doors of rich people and asking them to invest tens of thousands of dollars in something that is really just a bunch of guys with some ideas. But when you look at it from the rich people’s point of view, the picture is more encouraging. Most rich people are looking for good investments.”

Furthermore, talk to as many VCs as you can, even if you’re not looking for funding at the moment. Why? Basically, for two reasons:

- They may be on the board of a company who could be interested in financing you

- If you impress them, they may be less encouraged to invest in your competitors.

The most efficient way to reach VCs, especially if you only want them to know about you and don’t want their money, is at the conferences that are occasionally organised for startups.

Know your customer

This applies to startups and established businesses alike. All failed companies were not able to satisfy their customers at some point. Can you think of a firm that had a massively popular product and still failed? Graham refers to this as the “Hail Mary” strategy.

“You make elaborate plans for a product, hire a team of engineers to develop it (people who do this tend to use the term ‘engineer’ for hackers), and then find after a year that you’ve spent two million dollars to develop something no one wants. This was not uncommon during the Bubble, especially in companies run by business types, who thought of software development as something terrifying that therefore had to be carefully planned”.

To make a product that will generate demand, the startup needs to do their customer development: deliver a prototype and collect feedback for the purpose of further improvements or overhauls.

If you have money — don’t spend it all

The question is: one somebody gives you the cash, what should you do with it? “Refrain from spending it” is the short answer. For almost every startup that fails, the proximate cause is running out of money. While there may be numerous hidden rocks under the initial cash squeeze, the ultimate cause of failure is difficult to ignore.

Graham says: “During the Bubble many startups tried to ‘get big fast’. Ideally this meant getting a lot of customers fast. But it was easy for the meaning to slide over into hiring a lot of people fast”.

Graham encourages us to nurture a culture of cheapness. This will allow you to remain focused even when you receive some funds. While this money may initially make you feel wealthy, it’s crucial to realise you’re not. A rich company is one with large revenues. This money isn’t revenue. It’s your stepping stone towards making future profits.

Remember: time is money

If you launch a startup, it will take over your life to a degree you cannot even imagine. And if your startup succeeds, it will haunt you for several years at the very least, maybe a decade, maybe the rest of your working days.

As Graham writes, “Larry Page may seem to have an enviable life, but there are aspects of it that are unenviable. Basically at 25 he started running as fast as he could and it must seem to him that he hasn’t stopped to catch his breath since. Every day new shit happens in the Google empire that only the CEO can deal with, and he, as CEO, has to deal with it. If he goes on vacation for even a week, a whole week’s backlog of shit accumulates”.

Starting a successful startup is similar to having kids: it’s like a button you push that changes your life irrevocably. While it’s truly wonderful to have kids, there are a lot of things that are easier to do before you have them than after. You’d better be prepared for it.

Get your hands dirty

Founders with a technical background (programmers most of the time) would rather spend their time writing the code and catering for the tech aspects than worry about messy things like marketing, sales, investor relations, etc.

If you’re going to acquire users, you’ll probably have to get up from your computer and go find some. It’s hard work, but if you can make yourself do it, you have a much greater chance of succeeding.

As Graham puts it, “In the first batch of startups we funded, in the summer of 2005, most of the founders spent all their time building their applications. But there was one who was away half the time talking to executives at cell phone companies, trying to arrange deals. Can you imagine anything more painful for a hacker? But it paid off, because this startup seems the most successful of that group by an order of magnitude”.

Launching and developing a startup may be one of the most challenging things you’ve ever done. But if that is your calling – it might as well turn into one of the most rewarding experiences ever.